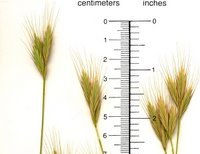

ehrharta, Ehrharta erecta, naturalized

Ehrharta erecta has only recently been noticed on the Preserve. In early December, 2005, at Bear Creek and Sand Hill Rd fence, the herbarium crew collected ten or more ehrharta, fruiting. Appearing at first blush like an onion-grass, the

small-flowered melic Melica imperfecta, it was dispensing its fertile florets far and wide among the tall cyperus and California blackberry. It can now be found along San Francisquito Creek in the Preserve, and is well-established around the Indian grinding rock at the beginning of Trail A.

Native to the Western Cape, it is one of a formidable South African contingent including Cape ivy, and yellow oxalis (Bermuda buttercup) that are colonizing, inexorably, significant portions of coastal California. (Bossard 2000; Sigg 2003). It is a challenge to walk anywhere in San Francisco or Berkeley and not find ehrharta. It was not listed in the 1958

A Flora of San Francisco, (

The Wasmann Journal of Biology 16: 1-157) nor in John Thomas (1961)

Flora of the Santa Cruz Mountains of California: a Manual of the Vascular Plants. It has colonized Stanford's prime garden areas including the

Inner Quad circles, and can be found in the

California Native Garden. Ehrharta propagates by seed and exhibits both upright and trailing growth habits. It is a member of a small old world grass tribe of perennials and annuals that has been classed differently by authorities into higher taxa/subfamilies (Gould 1983), and is currently classified in subfamily Ehrhartoideae, which also includes the California native

Leersia oryzoides.

A.S. Hitchcock And A. Chase wrote of ehrharta in the 1950

Manual of Grasses of the United States:

Escaped, Berkeley, CA (evidently from the campus of the University of California). Shows considerable competitive ability and may become of value in replacing some of the troublesome weeds.

Philip Munz noted in his 1959 A California Flora, "Naturalized on the Berkeley campus. . . Introduced from South Africa." Sigg (2003) says that it was collected by G. Ledyard Stebbins as "adventive [introduced but not yet naturalized] in Botanical Garden, UCLA Campus, Los Angeles, in May 1946," and asks whether this collection was the source of Stebbin's research material? Stebbins, an eminent plant geneticist and founding member of the California Native Plant Society, had earlier written that ehrharta "became established as an adventive in northern California about 1930." (Stebbins 1985). Dr. Stebbins wrote in The ladyslipper and I (p. 83) that before he experimented with ehrharta that it was "already spontaneous in a small corner of the Berkeley campus".

Dr. Stebbins introduced ehrharta into test plots in the San Francisco Bay region in 1943 as part of an experiment:

. . . 22 different plantings were made of diploid and autotetraploid [created by Stebbins in his lab] Ehrharta, some of which consisted of seed sown in 5 x 5 m plots . . . while others were started by planting well-rooted clonal divisions . . . Sixteen of the plots were on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, and two each in the inner Coast Ranges of Napa County, the campus of the University of California at Santa Cruz, and the town of Carmel. (Stebbins 1985).

He noted in the 1985 article "Polyploidy, Hybridization, and the Invasion of New Habitats" that the unaltered specimens were reseeding in most of the plots, and had spread extensively into surrounding areas. Of a Strawberry Canyon plot:

For several years . . . little change was noticed, but about 1965 ehrharta spread extensively westward. The plants colonized relatively diverse areas, some of them in hard-packed soil and others in well-drained areas under redwoods.

Dr. Stebbins wrote about the experiment in his memoir:

Of the 10 sites in which I had planted seeds, only three gave results after the first generation, and in only one of them was the autopolyploid at first superior to the diploid planted next to it. Between the 10th and 15th generation , even this superiority disappeared, and in 1970, 26 years the original planting, the diploid spread first over a few meters and later over 100 meters beyong the original planting while the autotetraploid was almost completely confined to the original area. The superiority of the diploid over the auto tetraploid increased until 1984, 40 years after the original planting.

Time will tell how persistent and extensive ehrharta will become at Jasper Ridge.

image source: California Invasive Plant Council: Invasive Plant Inventory

References (* = in JRBP library)

Bossard, Carla. 2000. Invasive Plants of California's Wildlands.* http://groups.ucanr.org/ceppc/Invasive_Plants_of_California's_Wildlands/

Gould, Frank and Robert Shaw. 1983. Grass Systematics. 2nd ed.*

Hitchcock, A.S. 1950. Manual of Grasses of the United States.*

Jepson Online Interchange. http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/interchange.html

Munz, Philip. 1959. A California Flora.*

Sigg, Jacob. 2003. "Triple Threat from South Africa." Fremontia 31(4):21-28.

Stebbins, G.L. 2007. Ladyslipper and I. Missouri Botanical Garden.

Stebbins, G.L. 1985. "Polyploidy, Hybridization, and the Invasion of New Habitats." Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 72:824-82. In JSTOR from Stanford IP addresses: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0026-6493%281985%2972%3A4%3C824%3APHATIO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-5

Some naturalized annuals

Some naturalized annuals